We do not know exactly what Mr. Robert Gates, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, thought during Shangri-La Dialogue in 2009, when he looked at India as a Net Security Provider in the Indian Ocean Region. We also do not know what Dr Manmohan Singh, former Indian Prime Minister, during the foundation stone laying ceremony of Indian National Defense University in 2013 meant when he thought that India was well positioned to become a net provider of security in the immediate region and beyond.

India officially endorsed it in Maritime Security Strategy while also deliberating on the extent of ‘immediate region and beyond’. Many intellectuals and defense specialists have tried to make sense of what it means, however, officially there is no common understanding; neither in the United States nor in India. Yet it may mean significantly different to both. One may see it as a compulsion, other as an opportunity. Lesser leverage is available to the earlier.

Old Plot – Push Back Vs Push Out

There should be no doubt that the old play book is out in the Pacific. It is push back vs push out; this time only the direction is different. Maritime powers do not like maritime competition, World Ocean is witness to that. What the United States is doing and is likely to continue doing for at least foreseeable future is to challenge China to follow a rule based order. Trade war, sanctions, foreign military support etc. may be new terms but not to the Pacific.

Japanese experiences from 1937 to 1941, when the U.S. administration under President Franklin D. Roosevelt started supporting the Chinese and tightening restrictions on Japan, are enough to point to their repetition. The U.S. was a much larger naval power than Japan even after it attacked Pearl Harbor. Because of the simple fact that despite the U.S. Atlantic first policy, U.S. armed forces could generate and maintain significant numbers in the Pacific. Japan could not exploit that short window of opportunity that Yamamoto knew was essential.

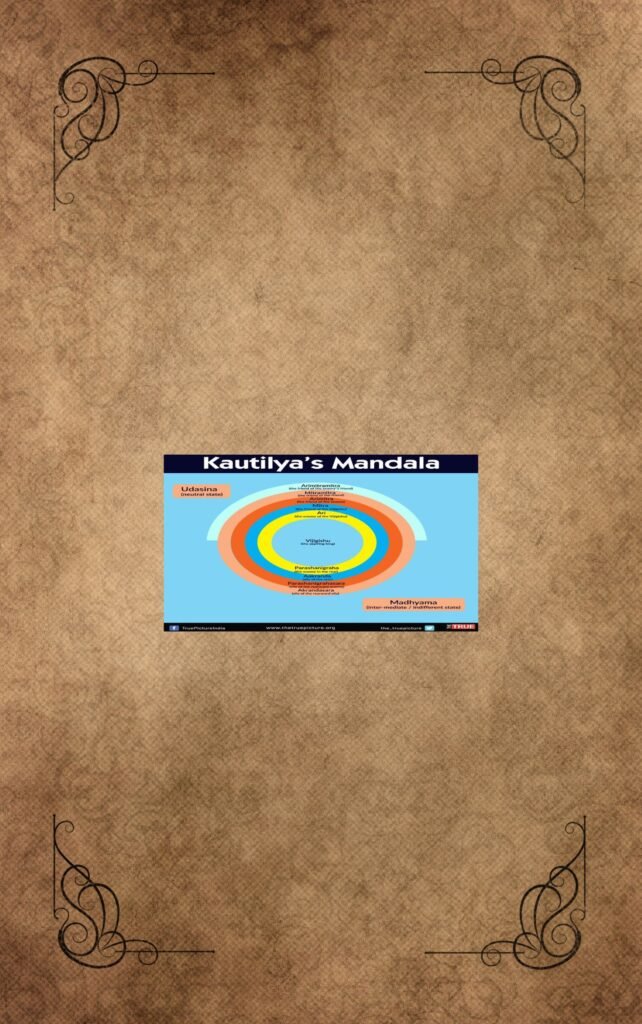

So what has changed that made the U.S. Secretary of Defense to say, ‘we look to India’? Answer lies in geography, capacity and technology. Geography favors China in the South China Sea especially when Taiwan is considered as the objective. Geography favors India in the Indian Ocean because it influences critical Sea Lines of Communication upon which China is heavily dependent for energy and raw materials. U.S. capacity to generate combat power in the Pacific is significant but consecutive war games have clearly demonstrated that it is not sufficient.

Considering U.S. commitments in Europe and Middle East and hazards of a comparatively aging military hardware especially in the Navy makes it a compulsion for U.S. to seek partners. Lastly, it is technology. Sanctions on Huawei, microchip war, Chinese export curbs on critical metals and U.S. dependence on foreign manufacturers for her defense needs are all indicators of what is happening on the surface of the technological front. While the U.S. maintains the technological edge, the deeper problem is that China has and continues to close the gap considerably and at a much faster pace than anticipated while maintaining considerable leverage in manufacturing capacity and critical mineral resources.

What U.S. and India May Seek

From this partnership, the U.S. may seek to at least leverage Indian geostrategic position in the Indian Ocean in close proximity to important maritime choke points in the east and west. This geography may also provide opportunities for BMD deployments. For the sake of mutual interest, the U.S. would definitely like to see increased Indian naval presence in the Indo-Pacific region taking on a more leading role in the Indian Ocean Region especially Middle East to create space for concentration of U.S. military resources in the Pacific. When analyzed in terms of U.S. military presence and assurances, the Middle East is the dominant region within IOR. When seen from DOD perspective it is important not only at strategic level but also at operational level. Not to forget that India is one of the largest arms importer while the United States one of the largest exporter.

In the coming decades, greatest threats to India will be land based while greatest opportunities will be sea based. While significant developments have occurred in other domains, with the United States being a maritime power, greater buzz is created when India and United States navies collaborate. That is likely to remain the natural course of military engagements with increased frequency in the Indo-Pacific.

India of course eyes enhanced prestige and great power status along with securing her economic interests. In fact Prime Minister Modi has related the Indian National Flag’s blue chakra with the blue economy. India also seeks defense technology through Transfer of Technology with initiatives such as ‘Make in India’ where possible and bridging gaps in her capacities through procurements where required. For India, the U.S. also provides diversification in reliance from Russia to meet her military hardware needs. More significantly, advanced U.S. intelligence through space, cyber and ISR assets as well as niche technologies can serve as a force multiplier for Indian armed forces.

On the economic front, mixed responses and outcomes exist with regard to Indian initiatives in maritime and geo-economic domains, such as International North South Corridor with Chahbahar port in Iran as its terminus in the North Arabian Sea, Security and Growth for all in the Region (SAGAR) concept and more domestically focused Sagarmala project for port, shipping and hinterland infrastructure. However, India has gradually enhanced her gaze on the maritime commons.

Can It Happen?

So can India be Net Security Provider? To begin with, the Indian Ocean region is not homogenous, rather a combination of unique and historical civilizations, societies, religions, cultures, ethnicities and issues. Based on these the region can be distinctly bifurcated into Middle Eastern, South Asian, South East Asian, English and African entities. Like Europe since the Greeks era, many dominant powers have ruled large parts of Indian Ocean territories, however, none controlled the entire region. While, cross cultural influences and migrations have been a norm, all these distinct regions have their varying needs, strategic cultures and outlook when it comes to national security.

Clash of Interest

If you ask any Arab in the gulf about the national security threat they point their finger towards Iran. On the policy level U.S., the region and India have divergence over it. The U.S. sees Iran as a threat. All national security documents indicate the same. So do most Arab nations in the Gulf and Israel. A stalemate on negotiations on the nuclear deal, Iran-Israel continued grey zone tactics at sea , although warming up relations based on Chinese efforts but historically deep rooted clash between Arabs and Persians, Sunni Islam against Shia Islam and so on are indicators that this particular region is highly muddled.

Politically and economically the region is likely to continue to drift away from the U.S. towards more independent choices often conflicting with U.S. interests. Such as, indulgence in massive Chinese owned, operated or developed ports, infrastructural and communication network projects, trading relationships, talks of oil for other currencies rather than dollars, issues of oil production and price control to name a few. Militarily, this region is heavily dependent on western especially U.S. assurances, albeit these countries are finding it increasingly difficult to deal with U.S. when it comes to foreign military sales and attached end user restrictions as well as sales restrictions due human rights issues.

India and Iran are altogether a different story. India has historical and long standing political, trade and cultural ties with Iran. For India Iran is a cheaper source of energy and a gateway to Central Asia, the critical center of geography from the likes of Mackinder to Kaplan. As per World Bank’s statistics India is Iran’s third largest trading partner after China and UAE. Considering the large Indian population and businesses in UAE, a significant proportion of Iran-UAE trade dividends end up in India in the form of payment for material and other services rendered as well as remittances.

If India loses the Gulf it may find alternatives albeit at a great financial loss. If India loses Iran its route to CARS is completely lost unless Pakistan allows it. This geographical reality in itself should inform the policy makers in the U.S. and Gulf region about the Indian predicaments when it comes to policy towards Iran. Great power status is not attained if one does not have the capacity to influence the immediate neighborhood. It is not in Indian national interests to forego Iran over Gulf States.

Money Matters

India’s balance of trade is negative with the majority of Gulf States. India is a net importer and therefore a market for mainly energy resources from the Gulf. Similarly, the Indian diaspora is by far the largest among all foreigners living or working in the Gulf countries. This means that it is not the case of macroeconomics alone but microeconomics as well.

Much to the official denial and dislike from all sides, considerable informal economy also exists between these states from which Indians benefit more than the Gulf region. In terms of FDI in the Gulf region, China is far ahead of India. Also in terms of exports India lags behind. Therefore, while these countries rely on Indian human resources, in all remaining aspects they are not bound but rather seek an opportunity and economic benefits. They see Indians as their employees and India as a market not as a security guarantor.

Bitter But Culture

Third aspect is culture. Any student of history can easily point to the fact that seeking protection from the powerful is a norm of Arab power structure. Arab culture does not feel any indignity to live today to fight another day. It is a pragmatic approach to life. Nor the Arab history is shy of examples how sheikdoms have cultivated relations with various powers. However, India is in no position militarily to assume a protectors role for the Gulf States and the Arabs know it.

In addition, these countries, especially Saudi Arabia and UAE are gradually progressing toward sufficient military prowess to cater for their own defensive needs. AI and autonomous systems will considerably fill the gaps for them in defensive needs. Therefore, these countries are more likely to see India as a security partner in some aspects such as training, capacity building and countering non-traditional threats but definitely not as a security provider.

In Conclusion

Whatever both sides understand from the term Net Security Provider, the fundamental question is whether it is happening? Is India capable of providing that breathing space for the U.S. in the Indian Ocean region for it to concentrate more in the Pacific? Is the region itself ready for that? I believe it is neither happening nor going to happen. Answer is hidden in three basic aspects of policy, economy, and culture. The term net security provider, U.S., India and the region have far greater clashes in all three domains than actually realized. In terms of ideal versus possible, Net Security Provider may be ideal for both U.S. and India, but not possible. Security requires actions beyond paper.

About the author